“Your Second Wife” & Lady Dangerous

Credit: TOR

Story: “Your Second Wife”

I never meant to get into this line of work, though I cannot deny that I have always enjoyed being other people.

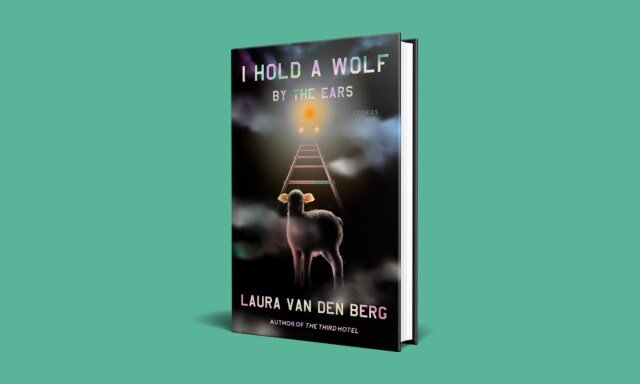

“Your Second Wife”, by Laura Van Den Berg, is remarkable daring and madly driven, packing within its short spill of words an almost improbable amount of ideas and topics, from the condemnation of the gig economy and dehumanization of workers, to explorations of grief and kindness and cowardice alongside ruminations about identity, murder, and the not-so-modest topics of the meaning of life and chaos theory. No big deal, really, just a smorgasbord of, you know, some pretty major human precepts. Originally published online in August of 2018 at Lenny (a now shuttered venture by Lena Dunham and Jenni Konner), the story is included in Laura Van Den Berg’s newest book, I Hold a Wolf by the Ears, a collection of short stories.

More photographs of dead wives came in the mail, and suddenly I had four part-time jobs instead of three and was too busy to apply to architecture school.

The story unfolds through the perspective of an unnamed woman who is a “grief freelancer” amongst her other three gig jobs. As a grief freelancer, she impersonates the dead wives of grieving husbands presumably, on the surface, because it’s good enough money or morally necessary, or both. At one point, the narrator, flushed with cash after six months of running the business for which the story gets its name—Your Second Wife—treats herself to dental insurance, a necessary health service. She doesn’t sleep with these men, something her sister routinely doubts from Australia, and, eventually, we understand (even if the narrator does not) that the need to impersonate other people is, and has always been, an interest of the narrator’s character since childhood.

“Your Second Wife” is segmented into smaller, titled sections that formally mimic something like a “gig” on the page, each one a small task pieced together and that allows for sometimes disparate ideas and narrative shifts to happen without a more traditional setup, using instead adhesive-like section titles to transition between. This joining of ideas is also gig-like: a series of unconnected experiences cobbled together out of chaos to create the semblance of a meaningful life, and something recognizable on its surface (i.e. a life, a story). The tone is muted, distant, and borders on absurdism: the narrator at one point is kidnapped by a man who takes her to the woods where the narrator, hands tied and tape across her mouth, doesn’t think about her impending demise but, instead, ponders about how the gig economy has reduced people to their services, how we “have stopped seeing each other as people, as fellow travelers on this dying earth; we just see a gig or an economy.” Which, you know, is absurd—not her criticism, but that the criticism would arise at this point in the story.

When I tell my sister about the incident with Beth Butler’s husband, I know she will plead with me to get a real job, but doesn’t she know real jobs barely exist anymore and not all of us are made to run off to Australia? The longer you stay in the gig economy, with its strange mix of volatility and freedom, the harder it is to get out.

There’s a necessary thought exercise and gateway-criticism contained within the gig-narrative of this story that’s actualized in the plot: the gig economy, which is more or less a patriarchal device, allows a person to gather up small jobs, and the incomes from them, into a survivable existence so that people can narrowly escape poverty, hunger, and homelessness, etc. The narrator, too, narrowly escapes Beth Butler’s husband who is this interesting metaphor for all of the terrible repercussions of a capitalist boot-strap economy ready to take advantage of a gig worker. When, under the section “Uh Oh, You’ve Been Kidnapped,” the narrator thinks that the “system is designed to keep us so depleted that we forget our sense of decency and become so savage about our own survival that we have nothing left to contribute to the common good” we’re hard pressed to disbelieve it, but, at that point in the story, the narrator is bound in the trunk of a car, certain her kidnapper means to kill her, and only reflects on her safety after she’s dropped this thought-bomb critique of the gig economy. At this point, halfway through the story, “Your Second Wife” removes its wig and rubber mask to reveal itself as a cleverly disguised polemic.

The polemic doesn’t seem to explore the gig economy, or the dehumanization of its workers, enough. Because of that, the narrative becomes a scaffolding to prop that message up. The narrator isn’t a part of the gig economy because she needs to be “or else” (or else she’ll starve; or else they’ll turn of the electricity; or else she’ll be homeless; an “or else” that many people in the gig economy face without their piecemeal jobs). Instead, she was architect school bound until she committed to becoming a grief freelancer instead, pursuing a calling, a deep need, in an otherwise chaotic world. Here, the story provides a clever explanation to tie everything together by introducing (in the last few paragraphs) this quote from meteorologist Edward Norton Lorenz, the father of Chaos Theory: “When the present determines the future,” the narrator recalls from her college days, “but the approximate present does not approximately determine the future.”

Translation: it’s all about the initial conditions.

That theory, popularized (for me) by Jurassic Park and the flapping of butterfly wings to summon a hurricane, is less about how random and unpredictable events inherently are and more about exploring the importance of initial/current conditions to project and predict future conditions. This is what meteorology is: looking at current global weather patterns and predicting where they may be in a day or a week. The chaos occurs the further out a projection goes as more and more unknowable facts join the current model. As another rich story element, Chaos Theory only shows up at the end as a way to gather all the many threads together and reinforces the idea of chaos as the monster under the bed instead of the knowable thing we don’t yet understand. This seems to undermine the spirit of Lorenz’s theory, and it feels like another aside that arrives suddenly, and what follows directly after is the hidden truth about how the narrator has always impersonated other people since she was a child playing hide-and-seek with her sister. “I agreed to play each and every time,” the narrator thinks in the very last line of the story, “because I knew that [my sister] would never beat me, not as long as she remained uneducated in the art of being both everywhere and nowhere at all.” This thought, and the entire end of the story, seems to focus on the narrator’s sister and their relationship and not on: the gig economy, grief, chaos theory, or even her daring escape from a murderer.

It’s in this final move that the story becomes wildly transcendent or confusing, when it emulates the character more than it explains, or explores, her as a person. Ironically, the character becomes a prop meant to extol the dangers of the gig economy for the reader and to show how it dehumanizes people and reduces them to their services—and in the final move the story renders the narrator to a messenger meant to deliver that message. But in that move the story somehow, and perfectly, impersonates the narrator’s focused and blind pursuit of her own motivations to be not only remain in the gig economy (because we don’t know if she must) and to chase a form of happiness through impersonation—and I can’t tell if this is the most amazing work of fictional jiu-jitsu to actualize a character-story symbiosis, or a flagrant bait-and-switch polemic that’s not fully committing to the reality and (ugly) necessity of the gig economy. And while I’m left absolutely baffled and considering the multiple ways the story and narrator wind up where they do, I’m more than willing to (and wanting) to believe that this is purposeful, and meaningful, if not chaotic. And if that isn’t a reason to drink, then I’m not sure I know anything anymore.

Cocktail: Lady Dangerous

Her lipstick colors were all classics: Lady Dangerous, Bruised Plum, Cherries in the Snow….I ordered her drink, an Old Pal, even though I can’t stand rye whiskey. I considered this flourish to be nothing less than an act of love.

Setting aside the way I couldn’t stop thinking about the literary koan “Your Second Wife” was for me, I was immediately intrigued by the call-out of a cocktail, the classic Old Pal, and the very exciting lipstick color of poor Beth Butler, Lady Dangerous. This week’s cocktail is riff on the Old Pal with a certain person in mind, someone who can meet become anyone and no one. Someone who escapes the trunks of cars and asks diner employees if they have alcohol while their hands are still bound. Bold, strong, suddenly gone—this is the very spirit of Lady Dangerous!

Recipe: Lady Dangerous

1.25oz Rye Whiskey

0.75oz Campari or Aperol (any bitter aperitif)

1oz Red Wine (I used Pinot Noir)

1 Teaspoon/Bar Spoon Benedictine

Add all ingredients to a mixing tin or cup, and add ice.

Stir for 40-60 turns.

Strain into a glass with or without ice (if you add ice, I would do less turns, 30-40).

Garnish with a lemon peel or slice.

Sip and ponder the conundrum about how the idea of chaos is a misnomer because, if you knew the initial conditions of a situation and all the variables, you could predict everything and it’s only your limited perspicacity that prevents you from avoiding the worse of life.

Maybe make a second drink.